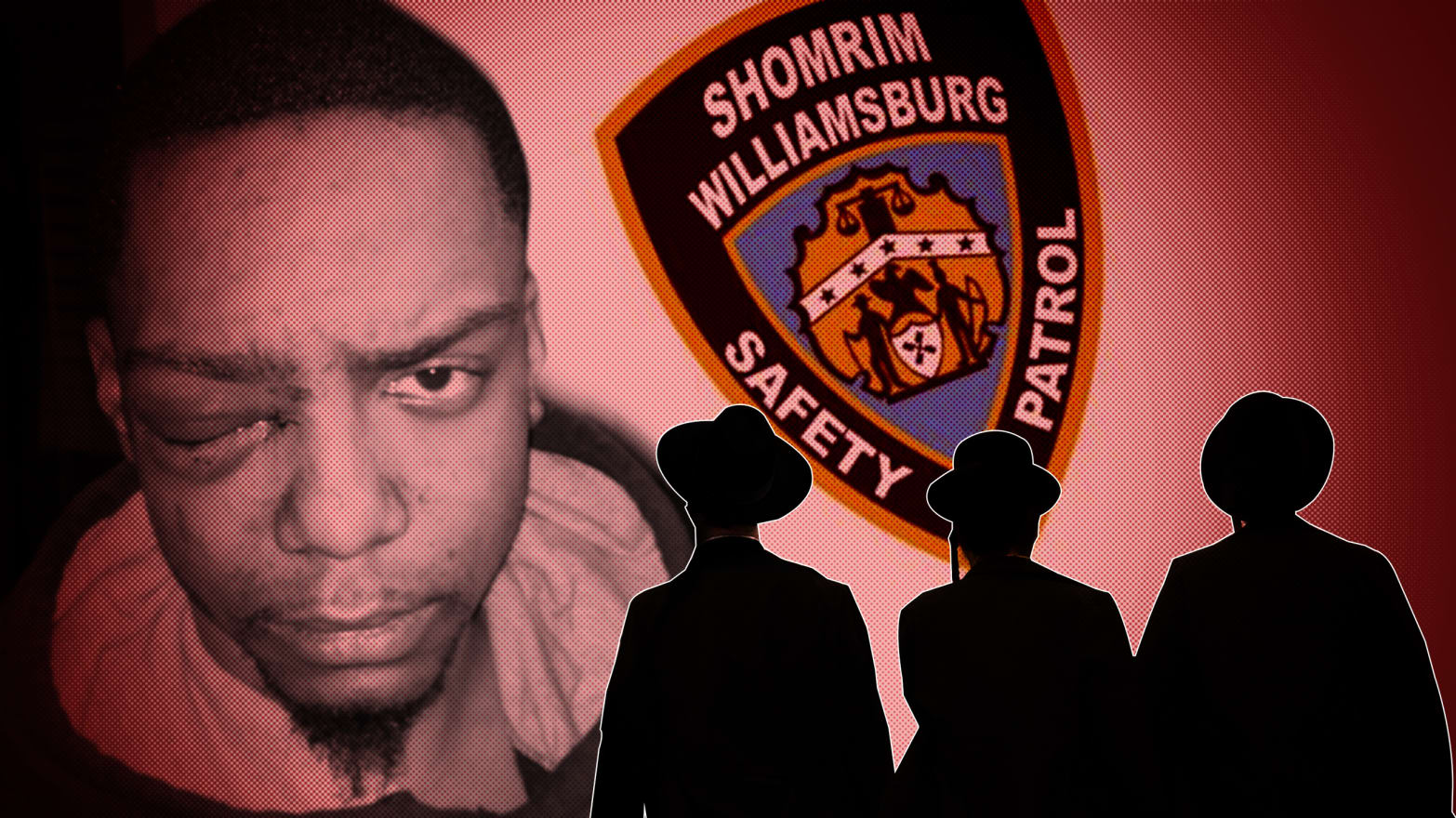

Meet the Shomrim—the Hasidic Volunteer ‘Cops’ Who Answer to Nobody

New York pols from Mayor de Blasio down have supported the groups, even as accounts of their rough conduct pile up.

Hella Winston

NYPD Inspector Michael Ameri shot himself Friday in a Department car hours after the FBI reportedly questioned him for a second time about a series of alleged payoffs made by members of New York’s ultra-Orthodox Jewish community—including several big donors to Mayor Bill de Blasio—to high-ranking officials in the NYPD.

That probe has focused on lurid reports of diamonds for top cops’ wives and hookers for those cops on free flights to Vegas, but it’s also put a spotlight on a longstanding nexus of shady dealings between New York City politicians, including the mayor, the NYPD, and the Jewish community’s own “volunteer” police.

A few months before killing himself, Ameri cut ties with one such pretend police officer, Alex “Shaya” Lichtenstein, the New York Post reported. Last month, Lichtenstein was arrested and charged with offering thousands of dollars in cash bribes to cops in the department’s gun licensing bureau in exchange for very tough to obtain in New York City gun permits.

Lichtenstein reportedly bragged that he had procured them for 150 friends and associates, charging $18,000 a pop and paying a third of that to his police connections. According to prosecutors, the scheme had enabled a man with a prior criminal history that included four domestic violence complaints and “a threat against someone’s life” to obtain a gun.

In the criminal complaint, filed in Manhattan federal court, Lichtenstein was identified as a member of Borough Park’s private, all male, unarmed volunteer security patrol, known as the Shomrim (Hebrew for “guards” or “watchers”).

The complaint did not identify any of Lichtenstein’s alleged customers, however, but sources knowledgeable about the Shomrim are skeptical that he was obtaining permits on behalf of, or for, the Shomrim as an organization. Instead, they argue, it is more plausible that Lichtenstein was operating as a freelancer—albeit one who likely exploited police connections nurtured during his time as a member of the group.

After all, it is not exactly a secret that the Shomrim—along with others from the ultra-Orthodox community who serve as unpaid liaisons to various city and state law enforcement agencies–maintain close relations with members of the NYPD, and particularly those who serve in their local precincts.

For example, news sites and Twitter accounts that play to an ultra-Orthodox audience are littered with pictures of Shomrim hobnobbing with high-ranking police officers at pre-holiday “briefings,” honoring them with “appreciation” awards at community breakfasts or charity dinners, and even engaging in friendly competition at an annual summer softball game.

But Lichtenstein aside, it would be a mistake to conclude that for the Shomrim at least these relationships are motivated by the prospect of personal financial gain or status concerns, even though there’s no doubt that having an “in” with the cops can boost one’s standing in the community. Instead, access and influence are the means of achieving a more important communal goal: the freedom to operate as the de facto police force of their communities, but with backup from the cops in the most dangerous situations.

In some sense, it is almost as if the Shomrim view the NYPD as their auxiliary police.

***

The first of these Brooklyn patrol groups were formed in the 1970s in the Hasidic neighborhoods of Crown Heights and Williamsburg in response to rising neighborhood crime and the belief that the police were not up the task of keeping Jews safe. (The journalist and author Matthew Shaer traces the roots of the Crown Heights patrol to a Hasidic rabbi and teacher named Samuel Schrage, who in 1964 founded a group called the Crown Heights Maccabees following the alleged assault of Hasidic students by a group of black youth and the attempted rape of a rabbi’s wife by a black man.)

Today, Shomrim (and in some cases, rival groups known as Shmira) exist in every ultra-Orthodox neighborhood in Brooklyn (and in other ultra-Orthodox communities in the U.S. and abroad). The groups operate independently and, while their leaders are fond of characterizing them as the “eyes and ears” of their communities, responding to hotline calls about everything from vandalism, missing persons and attempted robbery to domestic violence and even sexual abuse, they do much more than watch and listen. In Brooklyn, they are equippedwith SUVs and cruisers tricked out with “police package” flashing lights, sophisticated two-way radio dispatch systems, bulletproof vests and outfits emblazoned with shields that look an awful lot like NYPD ones—all paid for by donations and, in some cases, government largesse funneled to them by members of the City Council.

While they lack the authority to make arrests, even with those similar shields, the Shomrim often do things like search, chase, apprehend, and detain.

Indeed, as the head of the Borough Park Shomrim explained to the Village Voice’s Nick Pinto in 2011, people in the community call Shomrim because “they want to see action right away, not get caught up in a lot of questions and answers…Not that that isn’t the right way for the police to do it—who am I to say they shouldn’t ask a lot of questions?”

But people also call Shomrim—as opposed to 911—because, after all, cops are outsiders. And outsiders cannot always be counted on to be sensitive to the specific concerns of the religious community, concerns that include the desire/obligation to protect other Jews from the long arm of the law. And so, while the Shomrim are not averse—and sometimes quite eager—to help cops nab a suspect who is not one of their own, they can be much less forthcoming when a fellow Jew is the suspect.

For example, back in 2011, the coordinator of the Borough Park Shomrim let it slip to the press that his organization maintained a list of suspected ultra-Orthodox child molesters they don’t report to the police because “the rabbis don’t let you.” While there are respected Orthodox rabbis who say the police should be called in cases of suspected abuse, their rulings are not being followed in many quarters of ultra-Orthodox Brooklyn, where this attitude has long stymied law enforcement efforts.

Those comments came in the wake of the murder and dismemberment of an 8-year-old Hasidic child, Leiby Kletzky, who had been abducted by his killer, a member of the religious communty, while walking home from school. When the boy failed to meet his mother at the appointed time, she contacted the Shomrim, who swung into action and mobilized a search; their first contact with police came over two hours later.

At the time, many in the community justified the delay by arguing that the cops would not have taken the missing-person case seriously until more time had elapsed (a claim the NYPD disputed, noting cases involving missing children are acted on immediately). Some members of the Hasidic community also acknowledged privately that another possible reason for the wait to involve police: The fear, reasonable or not, that even had the child been found safe, Child Protective Services might have opened an investigation into why the parents allowed their son to leave school unsupervised.

This instinct toward protecting members of the community—and the community as a whole—is a theme that emerges in stories ultra-Orthodox sources tell about instances where the Shomrim have allegedly discouraged victims of violence or abuse at the hands of fellow Jews from reporting those crimes directly to the police, or even urged Jewish business and homeowners to withhold security footage that might implicate a Jew in a crime.

Indeed, in the wake of Leiby Kletzky’s murder a Jewish organization was given a million-dollar government grant arranged by state legislators to operate a network of security cameras on city lampposts in the ultra-Orthodox neighborhoods of Borough Park and Midwood. The organization hired a private firm to operate the network and made the decision, together with Assemblyman Dov Hikind, as to where to install the cameras. Initial reports indicating that the NYPD would have access to the footage only after making a request to the private firm caused a firestorm of protest from civil libertarians and those alarmed by government funding of private security initiatives. Ultimately, when the program was unveiled, the company’s founder said that “the local Shomrim patrol organization would have no access to the cameras but that in any event of an ongoing crime, local law enforcement authorities will be given on-time access to a live feed of the cameras.”

There are also allegations circulating on blogs and in chatrooms about Shomrim members and leaders who abuse their power within these communities, taking protection money from business and using their ties to the cops to get their rivals picked up on bogus charges.

Shomrim leaders have repeatedly denied these kinds of allegations and because the people who recount such stories refuse to be publicly identified, citing fears of reprisal, their claims are impossible to fully investigate and verify.

The cops, too, are well aware of the power the Shomrim yield—power that’s also expressed in the cash the groups receive from city politicians—but, like the members of the religious community, are also reluctant to express their frustrations publicly.

A rare exception was when then-Police Commissioner Ray Kelly acknowledged at a press conference that the delay in notifying the police about Leiby Kletzky was a “longstanding issue with Shomrim” and that traditionally, “certain members of the community have confidence in Shomrim and go to them first.” But Kelly also added that the delay had apparently not hampered the investigation and praised the Shomrim as “a positive force.”

One possible reason cops might not want to publicly criticize the Shomrim is the fact, some say, that over the years the bigwigs in the ultra-Orthodox community have been helpful to them, particularly in aiding friendly officers secure discretionary promotions.

Veteran cops reporter Leonard Levitt last month offered this short, sharp item:

“Ethics Training? Following the transfers of four of the department’s top brass, Bratton announced the department was conducting ethics training for its top officers. Maybe they should start with a warning about the dangers of getting too close to the powerful and insular Hasidic community. Instructors might include Chief Joe Fox, former Chief of Department Joe Esposito and retired Chief Mike Scagnelli.”

That comports with the speculation of one retired NYPD official: “the simple way to connect dots is that guys like [former Chief of Department] Joe Esposito and [former NYPD Traffic Chief] Mike Scagnelli were, at one time, commanders in the 66th precinct. With such longstanding roots in the community, these uniformed guys and the machers stayed close as they rose up the ranks. With [Esposito] as the longest serving chief of the department, the [Hasidim] were in a wonderful position for over 12 years to exercise immense influence over many promotions.”

The former official continued, “(Chief of Transit) Joe Fox himself was a remarkable beneficiary of these discretionary promotions. Everyone loved Fox, and he was the longest serving Borough Commander of Brooklyn South by far. In the 1990s, he achieved three discretionary promotions in 3 years… all while the commander of the 71st precinct [which includes Crown Heights]. From captain to chief in three years, it doesn’t get any better than that.”

***

TO READ THE REMAINDER OF THE ARTICLE CLICK HERE.